Exodus and Liberation

February 29, 2024

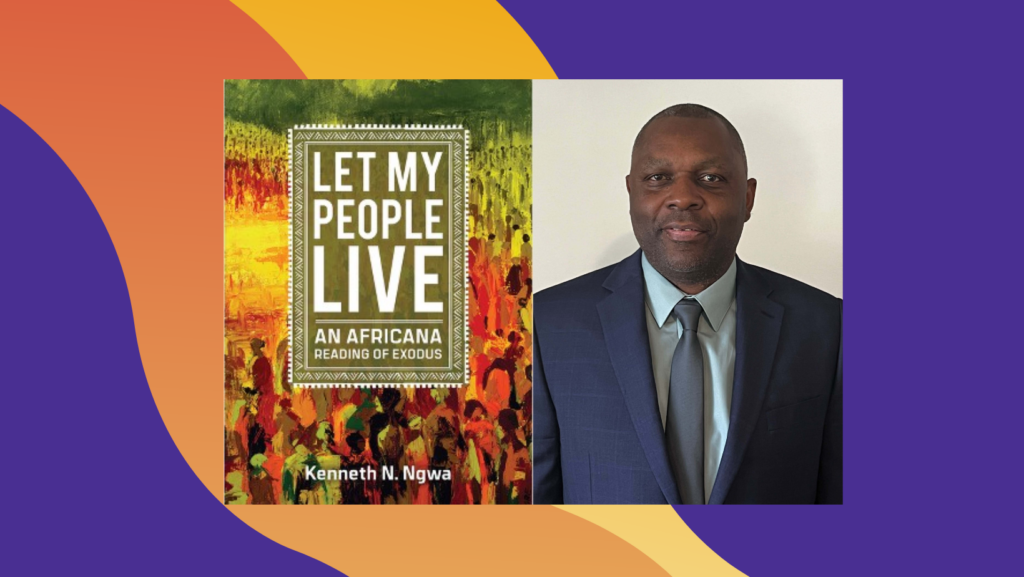

A book review of Let My People Live: An Africana Reading of Exodus, by Kenneth N. Ngwa, recently named Professor of Hebrew Bible and African Biblical Hermeneutics

By Aaron Dorsey

A commitment to life precedes, directs, and extends beyond efforts towards liberation. This is at the core of Kenneth N. Ngwa’s argument in Let My People Live: An Africana Reading of Exodus. Ngwa demonstrates how the book of Exodus responds to the triple consciousness—the consciousness formed by imperial violence and domination both in the biblical text and in contemporary imperial projects. Imperial violence produces consciousness of erasure/death through necropolitics, alienation through displacement, and singularization in the process of squashing multiplicity.

Ngwa does not believe that Exodus simply describes this triple consciousness. Rather, he examines how Exodus as a story, and the many exodus motifs that peoples throughout history have developed, move oppressed people through the triple consciousness onto reinstituted communal life. Exodus is a guide for the kind of communal storytelling that is required to move through the triple-consciousness without erasing the history of oppression. Ngwa invites the reader to see how the midwives, Jochebed, Miriam, and the Egyptian princess respond to erasure and policies of death in Egypt, how in the Wilderness the Israelites must respond to displacement by creating renewed relationships with the earth, and how at the Mountain Moses is confronted with the temptation of singularity in the form of becoming the strongman or the single father of the people. Each of these liberative responses to triple consciousness are not products of struggle for Ngwa, but rather they flow from commitments to human and non-human life and community that exist prior to struggle and are expressed anew within struggle. Ngwa writes, “The urgent depiction of exodus as departure from an oppressive nation-state house and machinery is formulated and encapsulated in Moses’ divinely inspired clarion call: ‘let my people go.’ But that call is more than an episodic manifestation of negotiation between Yahweh and Pharaoh. The call signifies an equally perennial and persistent call, ushered through voices from below, a call better represented by the words, ‘let my people live.’”

Ngwa’s commitments to Africana life, both on the continent and in diaspora, guide his reading throughout Let My People Live. Particularly helpful are Ngwa’s observations on how the challenges that anti-colonial wars and efforts faced have transitioned into the challenges now confronting postcolonial African nations. Though Ngwa does not cite Frantz Fanon, many of his concerns match those expressed Wretched of the Earth. Both realize that there is a possibility, which has become reality, that the postcolony can push out the colonizer while maintaining the structure of colonization. Fanon, for example, refers to the petit bourgeois, the native elite who are able to take the places of the white colonizer without changing the colonial system at all.

Ngwa reads this phenomenon through the story of Moses, who is adopted into the elite culture of the Egyptians, but whose authority on the basis of his Egyptian enculturation is rejected by the Hebrews. Ngwa argues further that Moses is a model of an anticolonial leader who resists the option to become a strongman—rather than accepting the ability to father the nation after the Israelites worship the golden calf, Moses pleads for the continuation of Israelite multiplicity. Fanon, recognizing that colonial administrations developed African colonies for the purpose of extracting resources and not for producing conditions for life, argues that a critical task of the postcolony is to reengage the natural environment. After retelling the story of Wangari Maathai and other Africana women involved in Afroecology, Ngwa offers an analysis of Miriam as the prophetess who listens to nature, who gives voice to the water, and who endeavors to make the Wilderness hospitable for the people. In this way, Miriam demonstrates how a commitment to the earth can resist alienation that (neo)colonial systems produce between the earth and human communities. By reading Miriam along with contemporary efforts, Ngwa demonstrates that Africana women are indeed already engaged in restoring relationship between humans and the environment.

What Ngwa brings adds to Fanon’s anticolonial analysis, and to de/postcolonial discourse, is a suggestion for how to move beyond these diagnoses. Ngwa hopes to offer Exodus as a story upon which people can model their own exodus motifs, stories that will be necessary to imagine a liberation that is more than an escape from an oppressive power. Rather, liberation, as Ngwa repeatedly states, will not be achieved until systems based on erasure, alienation, and singularization are replaced with ways of living that foster connection and community between humans, between humans and non-humans, and between creatures and the earth itself.

Aaron Dorsey is a Garrett-Evangelical Ph.D. Student studying the Hebrew Bible, and the recipient of a 2022 doctoral fellowship grant from the Forum for Theological Exploration.